There is a distinct moment of revelation that occurs in everyones life at one stage or another when you figure out your parents are, in fact, just people. That when you were growing up they didn’t actually know what they were doing most of the time. It’s a freeing and utterly terrifying epiphany. It reshapes the past as you look back to see that they were just doing their best at pretending to know what they were doing and raise you accordingly. It’s as if you’ve figured out how a magic trick was pulled off. That the dove produced from thin air was in fact a cruel caged mechanism concealed beneath the sleeve. This is the unique perspective Scottish filmmaker Charlotte Wells slowly reveals in her dizzying debut ‘Aftersun’.

” There is a specific texture to the visuals of Aftersun, one of reserved and mature filmmaking that is even more remarkable when you discover this is Wells first feature.”

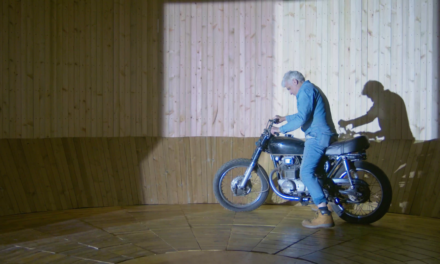

The film revolves around a summer holiday in the late 1990s. 11 year old Sophie, played by Frankie Corio in one of the years most remarkable performances, is taken to Turkey by her young father played by Paul Mescal. There is a specific texture to the visuals of Aftersun, one of reserved and mature filmmaking that is even more remarkable when you discover this is Wells first feature. She has this pinpoint precision in her visual choices that reminds you of Claire Denis or, closer to home, that of Lynn Ramsey. The visuals are evocatively simple in expressing large concepts; the strobe lights of youth in opposition to the overpriced carpet of adulthood. She decides to focus momentary poetics that really places you in the perspective of a child trying to come to terms with a world that is much larger than herself. It also works to position us with the older Sophie, looking back at something half remembered, trying to find clues to a reality outside of her own perspective. There is an excellent moment in which the camera sits on a Polaroid as it develops, slowly coming into fidelity, moments gradually fading into view.

Charlotte Wells mentions that the seed of the idea for the film had buried itself into her mind after watching old video tapes of her grandmother and aunty from the late 90s. She mentions a specific moment in which her aunty places the camcorder down at the end of the room and her grandmother asks if the camera is off, to which her aunty lies and says that it is and just watches them have lunch together. It’s an innocuous human moment that could existed within the films universe and is very telling of the wider ideas placed upon ‘Aftersun’. A lot of the visual diction stems from the use of the handheld digital camera that the father has brought on the holiday. The idea of capturing fleeting moments whilst missing the wider truth becomes a key part of the film, that there is always a performative aspect to that which is filmed. This idea continues even once the camera is off, whether it be the dad having to pretend to be more mature than he is or Sophie, who is at that age where you are clawing away from childhood. Then inversely there is future Sophie who desperately wants to return to this past.

There is a moment in which father and daughter float on a buoy in the Mediterranean as Sophie recounts a clumsy kiss she had with another boy at the resort. The father says that she can always talk to him about these kind of things as they, very pragmatically, discuss their emotions. It’s heartbreaking because we know, and future Sophie knows, that this will not always be the case. That these moments of honesty are fleeting and slowly retract over time, a Polaroid developing in reverse.