There’s something deeply fascinating about watching oneself on old home video tapes. I found myself in one such trance a few weeks ago. While it was wonderful to reminisce about my childhood, it was strange seeing my 5-year-old self trapped inside a segment of life which can be eternally replayed, but never returned to. Images like these offer us the refuge of remembering who we are, who we’ve seemingly always been. However, the sanctuary of memory has a dark underbelly. Film can be both the rug and the cruel hand that pulls it out from beneath us, exchanging self-affirmation with the spiralling vertigo of lost time and irreversible change. Luke Fowler’s Being in a Place: A Portrait of Margaret Tait, grapples with these slippery notions of selfhood, loss, memory, and poetry, and how they figure within the medium of film. Fowler undertakes an elusive search for Margaret Tait – one of the first Scottish women filmmakers and a pioneering artist and poet – by collaging materials from her archive and mirroring her experimental techniques.

“[Archival] images like these offer us the refuge of remembering who we are, who we’ve seemingly always been. However, the sanctuary of memory has a dark underbelly.”

The captivation that old home movies exert recalls the myth of Narcissus, who finds himself paralysed in self-love as he gazes at his own reflection on the surface of a lagoon. While the myth is often interpreted as a cautionary tale, warning of the dangers of vanity, I am much more taken by Maurice Blanchot’s counter-reading, which discloses a deeper secret hidden within it. “What is mythical in this myth” he writes, “is death’s practically unnamed presence – in the water, in the spring, in the flowery shimmering of a limpid enchantment”. He does not gaze at a spectacle that assures self-discovery and identity, but a perilous image that “exerts the attraction of the void, and of death in its falsity”. In other words, Narcissus does not recognise himself in the water because his reflection is not fixed: it splinters into abstraction as the water ripples. He is not in love with himself; he is under the spell of that which eludes representation. Film can be both this ghostly apparition of people since passed, or changed, and the intangible reflective surface that prevents us from ever becoming one with this image. Seen in this way, the fascination that we experience in watching ourselves on screen is not the boundless satisfaction of self-love and identification, but the magnetic pull of the unknowable and the irretrievable that lies at the heart of reflection. What makes Being in a Place so mesmerising is this same search for the un-locatable Tait and the alluring glimmers of the poet, that spring from her absence. Fowler’s approach captures the instant in which, suddenly, the water tremors, the reflection is broken, and Tait escapes the clutches of representation.

Sourced: https://www.luke-fowler.com/works/being-in-a-place-a-portrait-of-margaret-tait/

One also often forgets Echo’s role in the myth. The nymph with no voice: she is condemned to echo her interlocutor for the rest of eternity, but only the last words of each sentence. Echo falls in love with Narcissus but she cannot reach him. When he rejects her, he cries, “may I die before what’s mine is yours,” to which Echo replies, “what’s mine is yours!” This adoring, yet incomplete, mimicry is embodied by Fowler’s admiring, yet fragmented, reappropriation of the materials from Tait’s archive. Structured around a double dissymmetry between the two decentred subjects of Tait and Fowler, the film engages with an exchange of impressions, echoes thrown back and forth across the boundary of death.

Several of Fowler’s films are posthumous elegies, assembled from the artefacts and traces left behind by marginalised, little-known, or misunderstood figures. There is no predetermined conclusion to his documentaries. We learn with Fowler as he shoots, he looks backwards, reflecting on the conditions and limitations of the film itself. Laying bare the ever-evolving and unpredictable nature of filmmaking, his films rob us of the security of a beginning, middle, and end. The subjects that he investigates are too divided, too precarious, to afford their viewer the comforting identification coherent characters traditionally exert. Replacing the product with the process and the didactic with the poetic, Fowler also evades an all-too-common pitfall in documentary filmmaking: claiming absolute objectivity. In this way, each of his films is remarkably thoughtful, reopening the cold cases of each of his subjects, whether the general consensus had been sensationalised, oversimplified, or simply neglected.

Tait is no exception. She was a unique and pioneering experimental filmmaker who went against the current of her time. Her work escapes categorisation, engaging with poetry, essay-filmmaking, portraiture, and animation. She perpetuates the age-old Scottish tradition of forging an intimate connection with the land through poetry, emblemised by the likes of Robbie Burns and Nan Shepherd. Tait’s processes circumvented the trends and emerging patterns of her own time. As Sarah Neely writes, “her experimental methods were frequently misread as ‘unprofessional’ by a variety of funding bodies, more focused on the strengths of Scotland’s documentary revival”. For this reason, she made most of her films independently, with limited budgets, sourced by herself, friends, or family. The physical limitations of being a one-woman film crew were counterbalanced by the creative freedom that working outwith the expectant gaze of a producer. On the other hand, this meant that Tait struggled to gain publicity for her films and, as a result, has been largely excluded from Scottish film history. This is where Fowler intervenes, shedding light on the shadows that history casts. However, he projects a light that traces the silhouette of a woman faced away from us. In other words, he does not simply replace one history – one beginning, middle, and end – with another. Instead, he foregoes the process of hierarchy, repression, and exclusion that gives history the illusion of coherence and wholeness in the first place. While the film has been carefully composed and glimpses of biographical details punctuate the film, Being in a Place does not recount Tait’s life or work in a chronological manner. In straddling documentary filmmaking and visual poetry, the film searches for that which lies beyond the grasp of words.

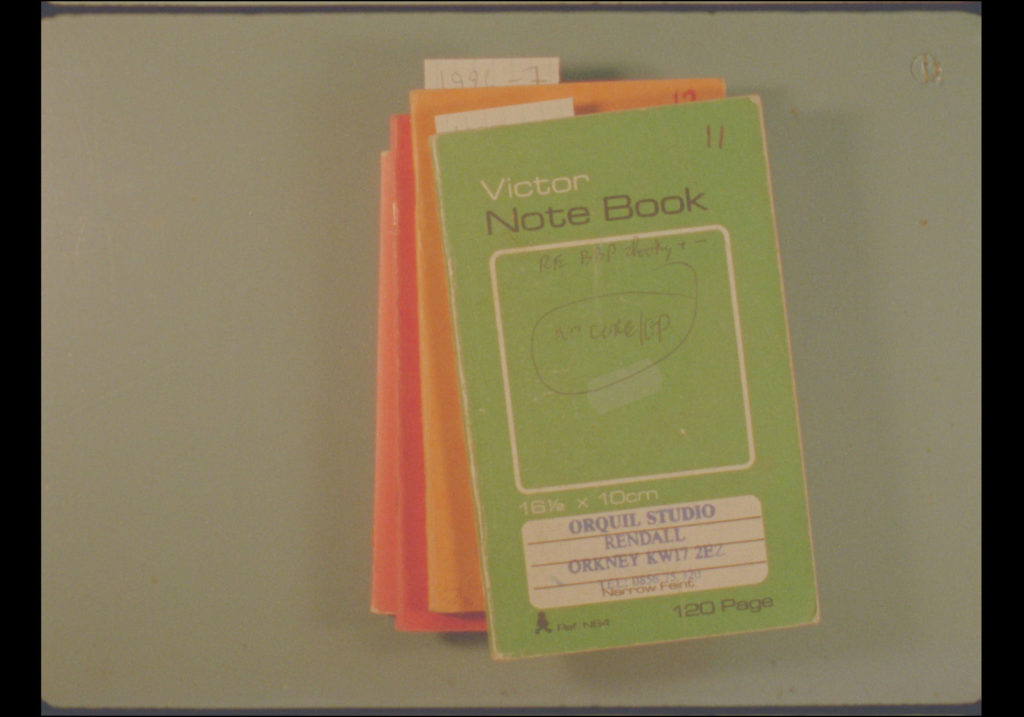

The film begins with notebooks whose pages have been dog-eared by Tait’s hands; the writing, a vestige of the thoughts she once had. This opens the collection of tangible fragments that Fowler accumulates, including notebooks, film paraphernalia, and correspondence belonging to Tait. A large part of the film tantalisingly reveals one instance of Tait’s perpetual struggle with funding, through rapid cuts and switches between written correspondence between Tait and Channel 4. Through this, we learn about Tait’s uncompleted film, Heartlandscape: Visions of Ephemerality and Permanence, for which the funding was, ultimately, revoked. The absent-presence of this film at the centre of Being in a Place, inscribes the stubbornness of death and the unknowable into the fabric of the film. Throughout this, Fowler intertwines visual fragments, in the form of excerpts from her films and Fowler’s own shots of his trip to Orkney, in which he emulates Tait’s filmmaking, through close-up shots detailing the land and fragmented, rhythmic editing. This is interwoven with audible segments, including recordings of Tait reciting her poetry, interviews with her, those who knew and knew of her, and a droning dynamic experimental soundtrack.

Sourced: https://www.luke-fowler.com/works/being-in-a-place-a-portrait-of-margaret-tait/

In her life, Tait appeared to oscillate between moments of community and solitude. Fowler, in turn, puts these experiences into dialogue. Drawing each one out from within the other, he distils Tait’s spirit from the community’s echoes and amplifies the silence between each echo. The images range from children playing in the sunshine to a ray of light piercing an empty room, accompanied by a solemn soliloquy. Tait’s voice emanates from a dark void. Her face is invisible, and we see what she saw. We chase her ghost. Every time we catch up to her, she has already taken another step.

The aim of Fowler’s practice is not so much to cement these pieces into a mosaic but to magnetise them in one place for as long as he is present there. To achieve this, the film draws attention to its own existence. We see Fowler holding his Bolex in the wing mirror of his car; we see his shadow stretch across a frame taken in the sunlit countryside, and the boom microphone makes several appearances. The sound and image are decalibrated throughout – Fowler has previously accredited the revered Robert Bresson for inspiring his use of this disconcerting technique. This asynchrony casts doubt on any sense of knowing we may believe we have. We take an extra moment to ascertain the source of each voice and are unsure which articulations correspond to which facial expressions. Using these devices, the film folds itself inside out, inspecting itself and drawing attention to its status as a film and as a process of learning.

Through its retracing of Tait’s life and work, Being in a Place explores the relation between mortality and art. In contemplating death, we may feel that we are standing at an impasse, marked by an insurmountable brick wall. It’s very difficult to approach the subject head-on, it would be painful and masochistic to run full-speed into a brick wall. Perhaps it’d be better to write your name, or someone else’s, on it, or shout over it and wait for a reply, or… project a film onto it. A film like Fowler’s brings forth the stark contrast between projected light and brick walls; between the glistening surface of a moonlit sea and the suffocating depths that lie beneath. The viewer is offered an ephemeral, oneiric encounter with the spirit of Tait while, at the same time, being dropped down a bottomless well of questions surrounding representation, memory, time, and death. The experience is equally emotional as it is intellectual. I think that had she seen the film, Tait would have been very moved.

Luke Fowler’s Being in a Place was shown at the Modern Institute on Aird Lane, February-March 2023. The film had its World Premiere at the Berlinale on the 17th of February and a UK Festival Premiere on the 5 March at the Berwick Film and Media Arts Festival. The majority of the material in the film is unpublished, some of it unfinished, and was sourced through the Pier Arts Centre, the Orkney Library and Archive, and Professor Sarah Neely of the University of Glasgow.

There’s still the chance to see this important contribution to Scottish film history. The film is set to be screened across Scotland in the venues that follow: The Comarty Cinema on the 16th of November, the Macrobert Arts Centre in Stirling on the 20th of November, the Cample Line in Dumfrieshire on the 15th of December, the Carinish Hall in North Uist on the 27th of January 2024, the Cromarty Hall in Orkney on the 24th of March, and the Pier Arts Centre in Stromness, Orkney, between the 29th and 30th of March.

References

- Blanchot, The Writing of the Disaster, 1980: 126.

- Ibid: 125.

- Sarah Neely, Between Categories : The Films of Margaret Tait: Portraits, Poetry, Sound and Place, 2016: 5.