My father is Russian, my mother is Russian, I am Russian too. My name is Slavomir and I was born in 1998 at the St Cyril Hospital in St Petersburg. Pavel, my father, was a founder of the Sintez Group – at the start a record label created by young Russian intellectuals during the collapse of the Soviet Union, now an oil smuggling operation moving millions of barrels to Europe every year. I’ve never publicly admitted to his role in this, but I can do it now. The dead don’t care.

Before you get the wrong opinion of my father, that he was like an oligarch or a gangster, I want you to understand that living in Russia during the 90s changed everyone. The immediate time after the collapse of the Soviet Union was akin to being dropped from a flying bus onto an island – an island where you had to forage for weapons and build houses. If you didn’t get more weapons, if you didn’t kill for them, somebody would come along and murder you. They’d build a house with your wood. They’d taunt you and do some awful dance over your cold body.

Everything he did, he did out of love for my mother and me, the little Slavomir, now dropped into a tilted city where danger lurked in every tower. Despite his crimes, he kept the soul of an old and reflective professor, one who smokes a pipe and reads the newspaper – a weary, wheezing dog on the rug in front of him, keeping him company. In his heart he was good, if anything he loved too strongly.

Like many wealthy Russians, we spent the summer in Turkey.

Antalya, specifically, a resort town on the Mediterranean Sea. I spoke Turkish then, far better than I do now, in addition to my native Russian. English I learned much later. The sky and sun were pastels, their reflection painting my face in happy soft hues. The streets were similar, a million little easter eggs masquerading as flats and shops. Mountain air is famous for its life restoring properties – a cold breeze entering your lungs, opening your eyes, making you aware of the body you occupy and the joy of existing in the present moment.

In Antalya once, I caught a fish. The smell of salt and skin, suncream and tea was much like that mountain air and I looked at the world as though I’d just been born. When I really gazed at that fish, looked at it without prejudice, I saw that he was smiling and I smiled too. The July light made rainbows on his skin and I returned him to the sea.

“Slova”, my father said, “come here”. It was 2008 and I was 9, enjoying a day at the beach with my family. When I waddled through the sand to my father, he mimed a whisper and I leaned close to his ear – “I think someone has shot me in the ass”. He opened his mouth as if he was going to say something more but I was already halfway through the city, running off in a huff. “How dare somebody shoot my father’s ass! My lovely papa, too kind for this world, the man who gave me my name”.

Kebab vendors fed dogs and tourists sat at tables outside cafes, slowly sipping lazy Sunday coffee as I sprinted by in a psychotic haze. When I turned the corner, I crashed straight into a blur of motion and colour, an amorphous shape knocking me down. I looked up from the pavement to see Hazal. She’s also 9. However the similarities ended there for you see she was a girl, local to the area. Hazal was slightly taller than me with a dark bob atop her head and sunglasses permanently hiding her brown eyes. It was rumoured amongst the Antalya youth that we had kissed last summer, I did nothing to stop the rumours and might have said one or two things to support them. “It’s terrible, those rumours”, I probably said to her at some point.

“Slova! What the heck! Watch where you’re going”. I said nothing, confused and winded. “Why are you in such a rush anyway?”, she asked, “you’re out of breath!”. I explained to her the facts as I knew them: my father had been shot in the ass and I was angry.

Hazal’s gaze immediately softened, “Pavel?”.

“Yeah, and his ass”, I replied, finally able to form a coherent sentence.

“Has the suspect been taken into custody and reprimanded?”

“There are no suspects! And I’ve not seen a single officer on the case”.

Her and I resolved that matters must be taken into our own hands, for the honour of my father and the safety of our community.

“It has to be another kid”, I said, thinking out loud, “it makes the most sense”.

“What do you mean? Another kid?”

“I’ll show you”, I replied, happy now at the thought of redemption. “Sir, sir!”, I said to the bewildered ice cream man, right next to us, who had watched the events in silence, “come stand over here”. The ice cream man obliged, for some reason, moving next to me and Hazal.

“Now if an adult were to shoot Mr. Ice Cream, they’d most naturally hit him in the chest”, I said, miming gun shots. “But a child, they’d hold their gun level with Mr. Ice Cream’s butt”.

Hazal nodded sagely, “you never hear about anyone getting shot in the bum”.

“Exactly. Let’s interrogate the others!” We darted off to the park, where kids would kick around a football until the sun became the moon and t-shirts became jackets. There were only a few there today: Misha, Hassan, Deniz, Ahmet. We were almost overdosing on bravado, the swagger in our step, cold and confident eyes broadcasting our righteous intentions.

“Did one of you shoot my dad in the ass?”

“What?”, the boys replied, almost in unison.

“Did one of you take my dad’s ass and shoot it with a gun?”

“What the heck are you talking about?”, Ahmet implored.

“His dad’s ass, it’s been shot, are one of you responsible for this crime?”

I nodded at Hazal, thankful for her rephrasing.

“No, we didn’t shoot anyone in the ass, we’ve been here all day”.

The twitching muscles on my face briefly relaxed, the sweat dripping down my face paused momentarily. Of course it’s none of them! They’re good kids just like me.

“I’m sorry for accusing you. It’s just my father, you see, he’s got this butt and somebody took a gun and riddled it with bullets”.

“I’m sorry to hear that Slova”, Misha said, shortening my name the way friends do, “is there anything we can do to help?”

Just then, Hazal noticed something. “If you’ve been in the park all day then why is there sand on your feet?”

The boys told us they had gone to the beach for lunch, that it had only been for an hour and they’d forgotten. Hazal and I looked at each other with grim understanding. These lads, once our friends, couldn’t keep a story straight. A conspiracy was afoot, and my dad’s ass was at the centre of it.

Hazal feigned a wave and yelled “Dasha, over here!”.

When the boys turned around to greet Dasha, we jumped them. We quickly took out their legs and slammed their chests, momentarily disabling them. Before they had a moment to react, Hazal began breaking Ahmet’s skull open with her backpack, heavy with books from the public library, while I jammed my thumbs into Misha’s eyes until his head popped like a bottle of champagne. Deniz tried to push me off him but I turned around quickly and punched him so hard his heart exploded. Hassan began to run and Hazal threw her bag at him, hitting the back of his head, knocking him to the floor where his head made a satisfying crunch under the weight of youth literacy.

We let out a sigh of relief and lay there for a moment, enjoying the sun and the slight ocean breeze rustling through the grass. This euphoria quickly died as I looked up and saw Hazal, making a puzzled face at a small scrap of paper she found on Misha.

“This is a receipt from the Ataturk Cafe, the one on the beach”.

“Date?”

“Today”

“Oops”

“Yep”

They were telling the truth. It couldn’t have been them anyway, I like those guys. When I see them next their guts won’t be strewn out their eyeholes and their skulls won’t be broken into a million pieces, scattered across the park, and I’ll apologise. In the meantime, however, the culprit is still loose and my father’s honour still at risk.

“Who just shoots a butt?”, Hazal asked.

“What do you mean?” – I spoke in Russian for some reason.

“They must’ve been trying to kill your dad, where is he now?”

“The villa, if we’re not too late! Maybe we can catch the assassin there”.

When we arrived at my neighbourhood we’d resolved to stock up on weapons. I distracted the security guard at the gate, Mehmet – he’d taken a liking to me ever since his son passed. I liked his son, too.

“I saw your son down at the pier earlier”, I told him.

“Slavomir”, he looked down softly, “you know he is no longer with us”.

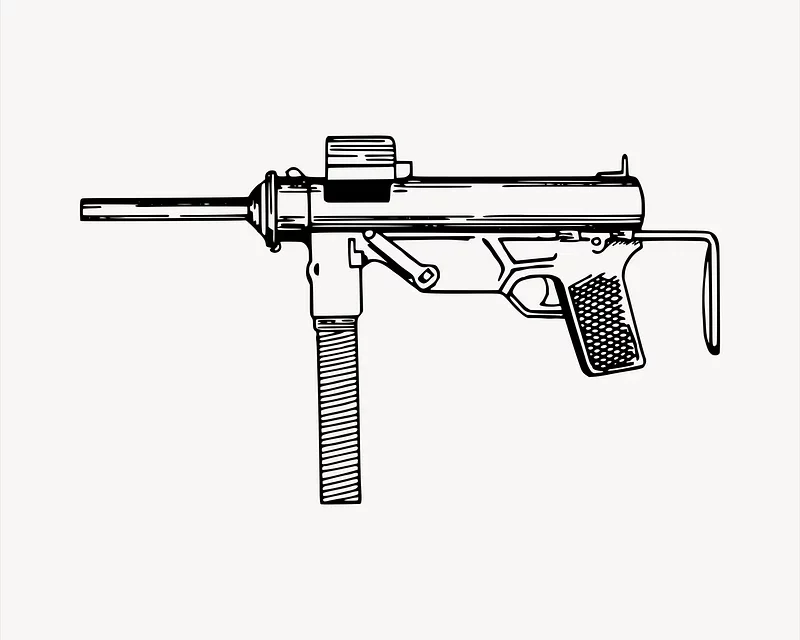

“Nah I totally saw him and he said he misses you and that he’s actually okay and not dead”. As I spoke, Hazal snuck into the security kiosk and gently dragged an uzi off the table. “Yeah he was actually super not dead, I think he was alive, even”.

Mehmet started crying, I cried too. His son was nice.

My father’s car was parked outside the villa. I snuck into the pool house and grabbed a steak knife from the kitchenette. I met Hazal next to the hedge and she told me she had seen someone around the corner, a kid like us. Why would they be lurking so near our house?

Hazal silently motioned for us to move and we slid along the garden wall, the sound of movement getting louder as we approached its source. At its loudest point, I stood up and grabbed the figure, heaving it over to my side of the wall and stabbing it’s throat with my blade. After the narcotic rapture of homicide left my brain, the figure took form and I recognised it as Galip, my next-door neighbour. I dropped his lifeless body to the floor and sheathed my knife, blood making a small brook amongst the caterpillars and daisies – mazy, lazily meandering through the dry summer grass.

A sudden noise gripped my attention and my head swivelled to Galip’s house, laughter inside. What are they cackling at?

“So there’s this ass right, attached to this guy, Slavomir’s dad, and I shot it!”

“Hahaha I was there too, it was my idea”

“Oh and I filmed it”

I could only picture that back and forth but it was a group activity, I had no doubt. My neighbours part of some twisted gang.

Their parents weren’t home, no cars out front. Hazal looked through the window – ten of them, the cousins over. Antalya is a very safe town, no one locks doors. We tiptoed through the back and into the kitchen where the voices became clearer. They were playing something, FIFA, an elaborate footballic ruse. As to direction, there was no doubt, the gangsters were in the living room.

I swear I must’ve started screaming before I kicked the door open. “Did you shoot my father in the ass? Did you?”

Ten faces, all shocked and bewildered, stared at me from their various couches and chairs, attached to their various bodies and torsos.

“What?”, asked the oldest, Aslan.

As I screamed back, Hazal propped a chair underneath the doorknob. “My father’s ass. Did you shoot it? Did you FUCKING shoot my dad’s cheeks, HIS ass?”

“Yeah, I would DEFINITELY shoot your father in the ass for no reason”, he said, rolling his eyes like a stone cold thug.

What he said – “for no reason” – made me feel sick. A psychopath. I gave Hazal a look and she knowingly held my gaze. In one fluid motion, Hazal lifted up the uzi and held down the trigger.

Reloading, repeat, reloading. ‘Til the faces were liquid there was no withholding. The blue sky and gold sun illuminated the reds and pinks spilling from silly carcasses onto the Persian rug that lined the ground. Cold black metal gleamed, beamed at me, as Hazal’s uzi built up the body mound. I jumped and slumped back on the wall, grinning and shouting as the bullets split the barrel, splat brains with vicious sound and vigour. Hazal was happy, too.

I ran to my dad. He sat by the pool, cold beer by his side. “Papa! Papa! I found who shot your ass!”

“What’s that Slova?”, his head lifted up from his book.

“Your ass, I found who shot it”.

He chuckled, the water reflecting off his eyes. “Slova, nobody shot my ass”.

“What? Then why’d you think somebody did?”

“Slova”, he stood up to hug me, “because there’s a hole in it”.