i. failing wildly ii. in praise of complicated narratives iii. hundreds of beavers review iv. designing a burning building by William von Lindvist

i. failing wildly

Sometimes success is doing three loads of washing in one day. I have come to the realisation that fulfilment is not a singular metric but instead a sliding scale set off kilter by self-doubt. I have dedicated the past 2 years to making a short film in search of that kind of elusive fulfilment. At a point, it begins to nag at you that the toil may not be worth it. That it has become a form of self-torture rather than self-expression.

This is something that I have had to think about more and more recently. As reality begins to cling to my skin the life of a starving artist starts to feel both vapid and romantically ill-fated. The life of a sufficiently full adult looks more and more appealing. The pursuit I was once accustomed to as a student has taken on a new dimension, between people being busy, having to work more and more, having to prioritise my time better and generally becoming less energised. The free-spirited, wide-eyed relationship I had with making art has become somewhat more complicated, and no doubt will become more so as time goes on.

This problem was not solved by a recent visit to Cumbernauld, as most problems commonly aren’t. I was there to visit my friend and frequent collaborator Paul in his home town. It was a long overdue catch-up and I felt if anyone was in the same boat as me in terms of creative flux it would be him. We first met outside a film studies seminar when we were 18. Since then we have started the longest and most fulfilling artistic collaboration of my career, working on a total of 7 projects together. He is often referred to as my work-wife. The Mike Nichols to my Elaine May, the Emeric Pressburger to my Michael Powell, the Joe Russo to my Anthony Russo.

I expressed my worries of literal and artistic bankruptcy to Paul. A concern that did not need to be elaborated on since it was constantly a wary reality for us both. Since graduating from university we have approached filmmaking from very different angles. Him, starting an apprenticeship at an acclaimed film school then going on to work on multiple productions only to decide to step back from the practical side. Me, going into a hospitality job, writing incessantly on the side and all round pretending to be above the screen industry entirely. Though veering wildly in our approaches we have remained close friends and have tried to work with each other whenever the opportunity rarely arose. And though we were seemingly on different career trajectories we had both ended up here, walking around a reservoir in Cumbernauld deeply unsure of what comes next.

Paul mentions to me a new job that he’s applied for, one that’s very much outside of the film world. He even spitballs the possibility of going back to retrain in something like mechanics. The question of why I am drawn to this work and what it is that I get out of it was evidently not just on my mind. On our many stints of filmmaking, enveloped within its manic throws, we have commented on how strange of a draw this very singular craft is. That there must be something wrong with our brains, both being compulsive detail orientated and driven to illusory perfection that we are at once repelled and deeply enamoured by. A process that is often tiring and unglamorous, and not to mention never coming together quite as it appeared in the minds eye.

The conversation winds and shifts from topic to topic, catching up on less overwhelming subject matter like Paul’s recent trip to Thailand and general life updates. However, I feel as though we are orbiting a conjoined thought. I sensed, however, we are maybe approaching the problem with different sensibilities. I have never seen this creative drive as something sustainable, economically or emotionally. I very much view it as a medium of expression, something that I always want to get better at and expand upon but aware that everything surrounding it is a bit dodgy and up for scrutinisation. It is typical of me to decide upon an art form that requires high volumes of labour and expenditure to function as my primary mode of creation. If only I was a graffiti artist.

Towards the end of our wander, we got back to the topic on the forefront of our minds. Paul mentioned how much one must give to work within an industry that is so precarious. That the work he was doing as a camera trainee was in some ways a glorified construction site worker with none of the union benefits. We also discussed how much the film industry itself was pivoting, the quality of actually good productions, large productions bringing in their own crews and the actors’ strike drying up what little work in scripted content there was. As we walked around a large cemetery (reality is rarely subtle when it comes to imagery), I thought about how this may be the end of a certain undefined era of our working relationship. Whatever was to come next would be reliant on funding and time that we could find using what little persistence we had left. It unsettled me to think about how much I needed him to function creatively. Maybe all of my perceived ability was based on our shorthand and how good he made me look on the technical side of things. Without Paul, I was potentially back to square one, an indecisive neurotic with some good ideas and no tangible way to express them.

As I got my train home I received an email from the person colour grading our film. I downloaded the link and watched what they had produced. They had done an amazing job, infusing the muddy analogue with vibrant colour and stylistic flourishes. I immediately sent the grade over to Paul. I started to make notes of small changes and the fulfilment I had been chasing, that joy that feels endless and impossible, returned.

ii. in praise of complicated narratives

The importance of looking after yourself cannot be understated. You must take time for yourself once in a while and indulge unashamedly. Turn off your brain and base your time on that which you know is an easy portal to excessive safety. We all have our own unique rituals for going about this, ones honed over time. One of my favourites a friend confessed to me, that I think about all the time, is their routine of playing the Sims and watching Would I Lie To You in tandem. Another unnamed source told me of their habitual viewing of endless YouTube videos by a very uncharismatic man as he tries to survive in the Arctic. For me, it’s watching films from the 1930s and 40s. They don’t have to be classics, or even that good. But something about that time period and the aesthetics; the beautiful people and lavish outfits, the swelling scores and odd sensibilities does it for me. Perhaps it’s the outdated techniques and morals that I can feel a safe distance from. Or perhaps, I’m mentally unwell. Either way, I was in the mood for such a cosy evening of mental un-exertion a few days ago when I decided to watch Midnight.

The film, starring Claudette Colbert and Don Ameche, is a screwball comedy about a nightclub singer who moves to Paris in search of work and becomes romantically entangled with a cab driver. She goes on to befriend a group of wealthy elites under the guise of being a duchess and has to maintain this charade in what becomes a comedy of manners. The film was exactly what I was looking for, a pacy screwball with a snappy script by Billy Wilder. What I particularly enjoyed about Midnight is how its narratives zigs and zags across multiple threads and constantly evolves. It begins as a simple love story between the cab driver and a down-on-her-luck singer but quickly morphs over its run time into an intriguing farce about class and the keeping up of appearances.

This is another thing I love about this particular era of filmmaking. How the narratives flow and bend and reform. It is something that is perhaps missing from modern filmmaking, a film starting as one thing then turning into something completely unrecognisable by its conclusion. These shifts are sometimes subtle, like with Midnight, or can be crazy pivots that you along with, for no better reason than it makes things more interesting. My favourite example of this is in Bringing Up Baby when suddenly a jaguar is brought into the story and you say to yourself: ‘ok I suppose that makes sense’. It is a trend that exists in the majority of these films. In fact, when I watch one and they have a more conventionally plotted story I am somewhat let down. They are all the more memorable for it, I have a distinct image from the opening of Christmas in Connecticut, a seemingly simple heartwarming Christmas film which starts with a scene on a submarine. I can’t remember why but the image itself has stayed with me for its absurdity alone and makes me want to revisit the film. History is Made at Night similarly has a somewhat simple romantic sheen but ends with them on a sinking ocean liner for no reason, except perhaps they had the set going unused.

These films’ trapeze-like narrative structures, though sometimes having a whiplash effect, hold your attention as you are not quite sure how things will eventually resolve themselves. They develop in such a complicated nonsensical manner yet feel reassured through the style and confidence of their telling. There are probably a couple of reasons for this storytelling trend. During this period they were only beginning to figure out how to tell stories with more of a focus on narratives afforded by the invention of sound. By taking a more segmented, literary slant makes sense. Or perhaps they were just testing out how far they could push these new tools to narrative extremes. Another reason is that audiences had different expectations of what a story could be at the time, with these films not necessarily having to fit within easily identifiable genres or structures or be marketed accordingly. The result is a plethora of studio films with bizarre almost surreal modes of communicating plot. By putting the characters through a variety of odd scenarios their complexities and contradictions can be examined just in a slightly madcap way.

It was around six o’clock when I was lying in my bed watching Midnight. It’s perhaps worth mentioning that I was also eating ice cream while I watched this rom-com starring all now long-dead people when my flatmate knocked on my door asking to borrow my razor. He came in and saw what I was up to and found it very funny. From his perspective, the situation looked either like a person deeply within their element or a cry for help.

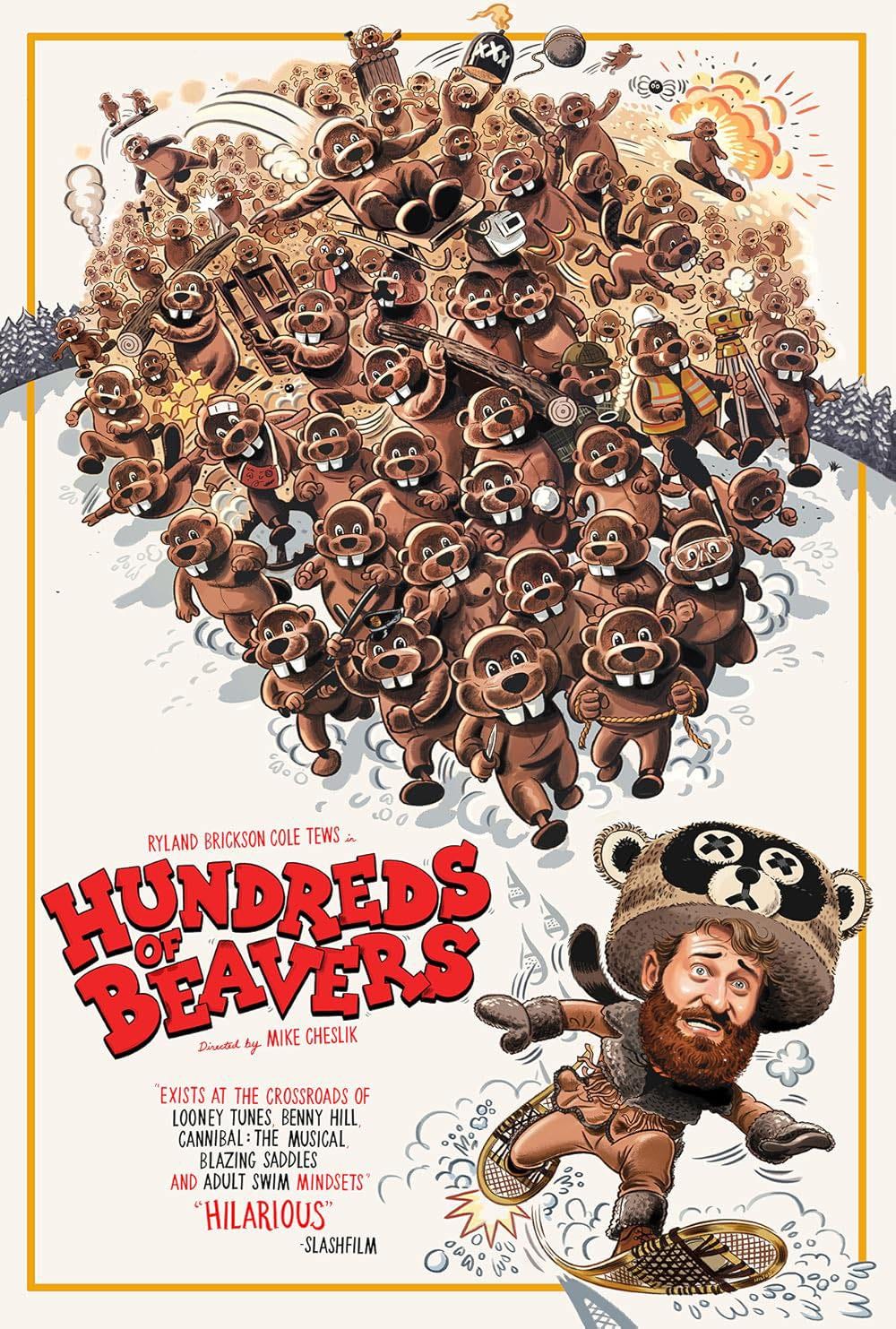

iii. hundreds of beavers review

“You’re missing the beavers!” read the message on my phone. I was hastily on my way to see Hundreds Of Beavers as part of a roadshow tour of the UK. I arrived, it turns out, with time to spare due to the chaos that was erupting in cinema one of the gft. True to my friend’s message someone in a Beaver costume was galavanting on stage as the main actor from the film took photos with a cue of audience members while selling blu-rays and posters. I found my friend and sat next to him and exchanged bemused looks at what was happening before us. As we had not yet seen the film, and I knew very little about it going in, the scene was even more bafflingly surreal.

The film itself lives up to the chaos and irreverence that preluded it. Made on a shoestring budget of $150,000 Hundreds Of Beavers is a mostly silent, black-and-white story of a hunter killing a variety of animals, beaver included, using increasingly elaborate traps. The film cleverly conceals its budgetary limitations through stylistic guises that charm more than they convince. The previously mentioned beavers are all people in shoddy outfits and the After Effects aided set pieces exist in a heightened way that sells its audacious sometimes cerebral ideas to cartoonish extremes. The conceit of placing this firmly within the stylistic reality of silent film slapstick is very clever and results in something that feels refreshingly new. Particularly the tone and structure feel all its own with the constant stream of gags working to keep you invested, if one doesn’t particularly land there is always another right around the corner. I think it helped watching this with a packed audience who evidently were very invested in the film which led to an almost midnight-movie energy.

Though scrappy in its aesthetics you can tell there is a lot of genuine craft behind it. Particularly the sound design working to sell the not so convincing effects and give weight to the action, making a lot of it feel as though it really hurt. I have seen a lot of reviews describing the tone as that of a video game but it reminded me more of, and just to warn you this is going to be a very specific reference primarily for me, but of Tim Heidecker’s Adult Swim show Decker which similarly uses green screen and compositing to its esoteric extremities.

Perhaps to the film’s detriment, it feels as though they have tried to fit in every possible idea they had into it and would maybe have worked better as a short film. At the very least as a 80 minute feature as at the moment, I’m not convinced it earns its runtime, with the middle second having a very repetitive structure that just about manages to remain engaging. It does in general feel slightly disjointed which maybe adds to it feeling its length at points. I wonder if the first self-contained act was the first thing they short and subsequently added to it as they went along.

I don’t want to sell this film short. It is very much a miracle of independent filmmaking in the truest sense. Though a lot of the comedy is admittedly not my kind of humour having the tone at points of a YouTube video, which I don’t mean as a bad thing but I realise sounds a bit dismissive. It proves as so often is the case that those outside of the film industry have much more scope to experiment and play with form. I would be interested to see what this filmmaker would be able to do with more of a budget if this is what he can achieve with next to nothing. I also appreciate this promotion via a roadshow on its second realise, being a clever and special mode of distribution. It’s something that feels out of vogue since the 60s, with the exception of the time Kevin Smith did it for that film where the guy becomes a walrus. It also shows an appetite from audiences to see such oddities of film, with most of this tour being sold out. Again this proves that film exhibition can be commercially successful when tailored to niche spectacle.

Once the film ended a Q and A followed that kept with the manic theme of the evening, the actor coming out dressed as a horse from the film and having a mock fight with the person in the Beaver costume. I have to say the whole affair was slightly painful to watch in the same way a pantomime always elicits second hand embarrassment from me. The questions were not particularly riveting either and I gestured to my friend that we could maybe leave. They whispered to me that they really wanted to see if the person in front of us would get a chance to ask a question. I had also noticed this going on in my peripheral vision, as they kept getting handed a microphone but before being able to speak someone else would jump in with ask a question. The situation had an appropriately exaggerated farcical quality to it.

iv. designing a burning building by William von Lindvist

This is an excerpt taken from a keynote speech by William von Lindvist at the Copenhagen Architects convention, which took place on Wednesday 12th March 2025. Lindvist, a noted architect and for-thinker in the field of destroyed and destroyable buildings, gave a talk entitled; ‘Post-Fab: Designing a Burning Building’. This is a small extract exclusively attainted by Splat! Magazine.

Frank Lloyd Wright was a dick. I don’t mean personally, I didn’t know him personally. But his contribution to the architectural pursuit renders him one. He made building design – perhaps accidentally, perhaps not – into a singular pursuit. Auteur architecture, don’t make me laugh. Architecture is the only art form that is quite literally done by committee. That is to say, it is not an art form at all but rather a series of mathematical problems and logistical issues to be solved into a shape resembling a structure. Needs and wants catered for, formed and objectified. If you wanted to make art you should paint a house, either its walls or as a picture quite frankly I don’t care. Art doesn’t interest me whatsoever.

I remember when I began my study of architecture at the University of Stockholm I was a strawberry blonde libertine with a mind full of geometry and a pocket protractor to prove it. On a fateful school outing to the Old Town we were tasked to observe and sketch some dynastically maintained heritage sites. A thought clearly bubbled into my brain as we looked at one of these limp wonky structures – ‘God, I’d love to blow that building up.’ At first, the thought frightened me, an iconoclastic insight that could only be summoned by a teenager full of angst and lack of sexual experience, and a pocket protractor to prove it.

Once I got over my initial disgust I examined the thought as you would an equation to be solved. It dawned on me that only in a buildings destruction can we see its full potential. After all, it is the end result, the final version if you will. The antithesis of a blueprint, not what we hope to achieve but what is eventually left behind. It is only in a building’s destruction that the synthesis of natural order is preserved. It reminds us that beauty is temporary, that our attempts to maintain order is vein and illogical, cruelly so.

When the Notre Dame cathedral fire began I leapt from my chaise langue and rang all the Parisian officials I had in my rolodex. “Let it burn, for heaven sake!” I exclaimed, putting forward my explanation of the beauty such sacred destruction would enact. Secretly within us all we want to see the end of civilisation. It is only in this destruction physicalised that catharsis is realised. Need I remind you of the destruction of that famous tower on that fateful day that changed history forever. I am of course talking about the tower of Babel, from which modern language was born. History is a forceful act of call and response; blitzkrieg to Bauhaus, jihadism to geometrics, forced migration to formalism. If this forced wordplay is not proof enough then you are indeed a lost cause.

Over the past 30 years, I have dedicated my life work to destroyed buildings. I have fought heritage foundations across the globe, and most recently been described as a potential threat on seven different government watch lists in the United States alone. My most recent initiative has been in the development of a series of buildings that are pre-demolished. That is to say, they have been meticulously designed by me and my team at Antwerp Universities division in ecological ruin to be built as if they were already in disrepair. We have carefully designed buildings from a variety of violent scenarios: house fire, drone attacks, aged decay, hurricane, buffalo stampede, the list goes on. Each artificially tells its own story, with its own rules and internal realities. I, like everyone, have my sceptics. A recent think tank described my project as a waste of government resources costing upwards of 28 million euros. But I posit to you, is not the erection of buildings that are not already destroyed more wasteful? It’s probably just going to get destroyed anyway.